Appelez nous : +212 (0)537-770-332

03.03.2022 Foreign students in Ukraine excluded from EU refugee law

European interior ministers reached an unanimous agreement on Thursday (3 March) giving almost everyone fleeing Ukraine safe refuge and extended rights to stay in the European Union for up to one year.

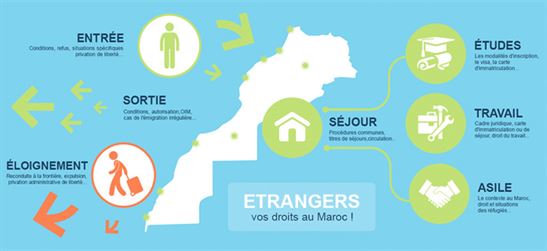

The plan offers immediate protection status to millions of Ukrainian nationals and long-term residents of Ukraine seeking refuge in the EU as of 24 February onwards.

But almost everyone else, like short-stay foreign students from Africa in Ukraine, are not covered and would instead be accommodated and fed in the EU before being repatriated to their home countries.

The exception has roused complaints from activists and advocacy groups who say everyone should be given equal rights and protection.

The International Organization for Migration (IOM), a Geneva-based UN body, said on Thursday it had received reports concerning dozens of nationalities facing discrimination while attempting to flee Ukraine.

Still, Thursday’s agreement marks a first for a European Union that has for years grappled over asylum as some EU states such as Poland and Hungary erect walls along their external borders to keep people out.

The speed at which the proposal was made and agreed over a span of four days is also a novelty for a European Union that has often been mired in lengthy disputes on how to help each other when it comes to migration and asylum.

But it also comes at a time with some suspecting Russia’s president Vladimir Putin of planning to use a humanitarian disaster to further antagonise the EU and Nato.

Putin’s tactics, used in previous conflicts in Chechnya and Syria, were to « terrorise populations and use columns of evacuated civilians to storm into cities », Mathieu Boulègue, a research fellow in the Russia and Eurasia Programme at British think-tank Chatham House, said in London on Wednesday.

The EU’s border guard agency Frontex has since deployed agents near the Ukraine border areas with Moldova, Poland, Romania, and Slovakia.

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine has forced over one million people to flee within a week, an exodus pace described by the UN high commissioner for refugees Filippo Grandi as almost unprecedented.

Open arms

So far close to 550,000 have gone to Poland, followed by 130,000 to Hungary, and almost 90,000 to other EU states, where most have been received with open arms.

The display of solidarity in Poland and Hungary for Ukrainians stands in contrast to their past refusals to host asylum seekers from Syria and elsewhere after over one million arrived in 2015.

They had also shunned efforts to distribute asylum seekers from Greece and Italy through various relocation schemes.

Now other EU states may later need to take in refugees from Poland and Hungary, should the numbers become too large for their respective national systems and Ukrainian diaspora to absorb.

The UN refugee agency has predicted up to four million people could flee. The European Commission says it could be 6.5 million.

Member states are being asked to discern how many Ukrainians they can handle with the European Commission tasked to relocate refugees around the EU, if needed.

« It’s a fluid system, » said a European Commission official, who requested not be named, when asked how the relocations would work.

Thursday’s discussions by EU ministers implements the so-called Temporary Protection Directive.

The never-before used EU law offers blanket protection rights to large groups of people fleeing war and persecution.

It means they do not have to file individual asylum claims, which would likely cripple national asylum systems.

« The standard trajectory that asylum seekers move through upon arrival in the EU, won’t apply here, » Hanne Beirens, the director of the Brussels-based Migration Policy Institute Europe, tweeted.

Unlike past arrivals of refugees and asylum seekers from other parts of the word, Ukrainians with biometric passports can travel throughout the EU for up to 90 days without a visa.

It means most are likely to settle in areas where they have family, friends or other connections. After the 90 days expires, the EU law protection law kicks in and entitles them to residency permits and other benefits.

Others will have to be accommodated in state reception centres. Should they fill up, a member state may need to request the European Commission coordinate a demand for the refugees to be relocated elsewhere.

Those demands have yet to be tested and for the moment are not needed, said an EU commission official. « That’s not the situation we’re in, » he said.

Source : https://euobserver.com/migration/154474?utm_source=euobs&utm_medium=email